She was 13 when Douglas Metcalf first came into her room in the middle of the night.

Rosina Claxton didn't know what it meant, but thought it must be God's will, because Metcalf was revered as Jesus by her's and a growing number of families.

"My initial reaction to the first time was 'thank God that's over and done with — I'm sanctified now'".

But there was growing dread when she realised it was never going to be over, mixed with guilt for the "repulsion I felt for the sexual act itself", she says from her home in Brisbane.

She became "smack bang in the middle of the inner circle". The community saw her as his secretary and an "unofficially adopted daughter".

"Privately I was a concubine. Everything was a double standard."

Camp David, more commonly known as the God Squad and less commonly as the Full Gospel Mission, was formed by its leader, Metcalf, in about the 1960s, but it was at its height in the 1970s. Families joined from all over the country, even attracting tourists to the 48-hectare camp in Waipara.

Metcalf died in 1989 but the truth about his past was not discovered until 1995, when women spoke out about his multiple sexual partners, prompting the walls to crumble around the still thriving community of about 200.

Claxton's parents met Metcalf at a Harewood transit camp waiting for government housing in the 1950s. He was knocking on doors as an evangelist, and despite her mother being initially skeptical, he prayed for her seriously ill friend, who then became well.

It "piqued her interest" and they were hooked along with others, many from military backgrounds.

"He was charismatic and powerful, and had a way of making each person feel special and setting one person against another. Right from the word go we were taught to revere Doug and never question."Those who had been through some sort of trauma, had idealistic views, or were inclined toward religion were "ripe" for the picking.

"Once you have a person's mind, you've got them." Claxton was taught that because of her Maori heritage, she had to be "sanctified".

"We were so brainwashed that I was taught that this was God's will for me.

"I was taken from my family into the Metcalf home [aged about 15] until I was 32."

Living a lie was horrible, and she often contemplated suicide.She would walk down to the river with her dogs and horses for relief.

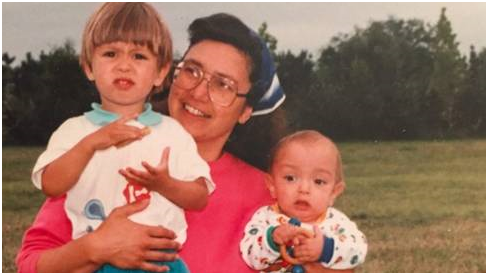

Rosina Claxton with her sons at Camp David in Waipara in 1994.

"I like to think my tipuna were with me then."

She fell in love with her now husband inside Camp David, but Metcalf refused to let her marry, saying she would be a "harlot". Months after he died, the couple married.

When they moved to Nelson, she was "horrified" to meet other Christians who said she belonged to a cult. She had three children under the age of five. It was when they took her third and newborn child back to the camp that she and other women "blurted stuff out to each other".

"Some of the other women said, 'yes, that happened to me'."

Word spread, and a majority of members fled within weeks. Being in a cult is like an elephant being held by the ankle not realising it has the strength to rip away the shackles, she says.

Not being allowed to think for themselves, or choose clothes, jewellery, make-up, or hairstyles.

She believes Metcalf already being dead was the only reason the community successfully disbanded.

She shed her scarf and long dresses, and felt the wind in her hair for the first time, but it was a long process to forgive and let go. She still looked over her shoulder wondering if she was being monitored.

First it was fear that "God was going to smite me down". Then frustration.

When a court mediation over the property's sale went ahead in 2006, she and her brothers walked through areas Metcalf used to take her.

Rosina Claxton has found peace in meditation, has been reintroduced to her Maori heritage, and is happy living in Brisbane after being Camp David leader Douglas Metcalf's concubine from the age of 13.

"It was all rubble and decay and I just wept."

"I just thought, 'What a waste of what could have been...without the sexual abuse and religious facade."

"Growing up in a cult is like growing up in a black and white photograph. When you come out of it you suddenly realise there's a lot of colour in the world."

There were plenty of good parts to Camp David life, says Claxton.

An extended and very close-knit family, with picnics, humour, and help always at hand.

"I went church to church looking for something as close-knit and I've never found it."

Moving to Brisbane was the first step to reclaiming her identity.

Meditation helped her, but others found peace in established North Canterbury churches.

Good and wise words can be found in each religion, but it is the power held by those at the pulpit that "can be dangerous".

Colin was a heraldic artist at Camp David in Waipara, North Canterbury.

The relentless preaching down to members, and the rules and regulations "got more oppressive as time passed".

There were staunch members who "would've killed for Doug".

"It was a time of absolute madness."

Her advice to others breaking free of a cult? Get support from other cult survivors."You don't just transition overnight, it takes years."

CAMP DAVID TODAY

The fortress-like walls of the old Camp David remain, within which some former members still live.

The Darnley Rd camp in Waipara is parallel to State Highway 1, alongside which weapons were buried by members preparing for a communist invasion.

Police raided the camp several times for its military equipment and weapons. It is thought weapons remain buried today.

If you were to duck through the miniature gate set into the larger iron entrance, you'd find buildings once humming with worshippers now languishing in a dilapidated state.

The camp is still home to some former members, with a business run out of a workshop owned by the current camp owner.

The high brick fortress-like walls of the past remain.

Machinery and old buildings are interrupted by a colourful garden of flowers, reminiscent of the floral patterns Metcalf encouraged female members to dress in.

Douglas Metcalf posing in a portrait during the height of his reign at Camp David in Waipara, North Canterbury.

Garry Love, whose engineering business is still next door, was one of many members so close to Metcalf he couldn't see what was going on.

"From my perspective, when you're right in something you can't necessarily see the way out of it."

When the introverted community fell apart hearing the truth about their deceased leader "everyone was scared".

"People were traumatised, they really were. They were frightened and didn't know what was going to happen".

Love felt betrayed.

"It just tore me apart."

"The original leader had some major issues, and he built something around himself to support his bad habits."

He "tricked some women into going along with him".

People had been hurt, and some of the things that happened were "still pretty raw". But his family had moved past it.

He believed staying, facing what had happened, and trying to break down barriers the community had built between it and the outside world was the best way to cope.

As a senior pastor at a church in Amberley, Love is now focused on helping the wider community.

"Camp David was all about itself."

"In some ways we found it difficult to be accepted in the local community because people have their suspicions. We had to weather all that."

His theology had been "totally overhauled".

"The things we believe [now] are very much in line with most churches."

Lenore Williams, who still lives in the district, has a philosophical view of her moving-on process.

Like the death of a loved one.

"Certainly the upheaval was very traumatic."

Like a beautiful tree laden with good fruit, with a bit of pressure, it splits and you realise the trunk's core is rotten, she says.

"Lots of areas definitely weren't right but we didn't recognise it at the time."

"Certainly it threw huge question marks on your own ability to discern."

"[You think] how did I get down this track? How blind was I? How gullible was I? How deceived were we?"

She never lost her faith, but got rid of "all the extra stuff".

She had become less dogmatic and judgmental about differences in beliefs.

"We definitely were at Camp David."

"None of us have it all together. None of us have the perfect anything. We need each other."

She believes most people were with Camp David because they had a genuine desire to do what was right.

There were a lot of positives — skills learned, friendships made.

"Some things are still very painful. It's not forgotten. Certainly forgiven. But I would say I'm a better person for having gone through it."

"Is the experience going to make you better or bitter? The choice is yours."

SHUNNED AND BETRAYED

Retired Presbyterian minister John Turton spent 12 years as part of the cult before experiencing the "cruel" cult control tactic called "shunning".

His final stand was a 14-page letter to Metcalf saying where the community was going wrong and what he thought needed to change.

"I became aware of God speaking to me and telling me to go."

Members were "liars and thieves", orders that came "from the top".

They were allowed to lie to employers about being sick when they were needed to work at camp, or to insurance companies about items being stolen. They also regularly shop-lifted in nearby towns.

Turton ran a shoe repair business in Amberley, and was told he would lose salvation if he left. But he did, and was excommunicated while Metcalf was still in charge in 1984.

Turton met his wife within Camp David, where they had two young children.

He equates leaving a cult to divorce grief.

"You can be bitter, resentful, extremely angry, you can find yourself bargaining in your head as to whether you want to go back."

He knows one previous member who won't allow any discussion of Camp David in his home. Others find solace in talking.

"It took me about nine years to deprogramme, or find myself again."

It was important to figure out why he joined, and why he left, in order to move on.

Writing his recently published book, Muddy Waters: I can see clearly now the reign is gone, has been helpful, he says.

"We would say we've moved past it and moved on."

"[But] you can find it comes back in your dreams."

Former member Colin (Stuff has agreed to not use his last name) has tears in his eyes as he recalls his father feeling his involvement was "quite the betrayal".

He had just arrived from the UK with his parents and siblings when he was introduced to "the Camp David way" through members in the Ohakea Air Force base at just 15 years old.

"We were in a situation where [his parents] knew that it was indoctrination but they couldn't break through it."

A keen artist, Colin proved his worth in the field of hard labour before he was allowed to paint the heraldic work — shields, flags and medals — Metcalf was so dedicated to.

He puts his quick recovery down to cutting ties after learning of the leader's "sexual nonsense".

He and his wife felt it was the best thing they could have done.

"When we realised what was actually going down we just got in the car and left. We left everything behind."

"We had nothing except the car and the [two] kids in the back and started a new life in Christchurch."

"A lot of people hung on for a while and others left in such a cloud of fume it put them in pieces."

For so long basic decisions were made by leaders. They were even angry when the couple chose their own family car a year before the community split up.

"As soon as you left Camp David and you could make decisions on your own, it was such a liberty."

He and his wife "just had to figure out things" as a team.

"She said 'I would kind of like to wear trousers', and I said 'Go on then'. We gave ourselves permission for things."

Aged 36, he trained in graphic design to earn a living to support his family and was finally able to repair his relationship with his parents.

"I think the knocks and bruises have definitely made me what I am now. A lot wiser, and a lot stronger."

"For a very, very long time [Camp David] would land up in your dreams."

"I dream normal dreams [now]."

Love hopes that lessons can be learned from Camp David.

"Looking back you wonder about a lot of stuff about [Metcalf]. If ever I meet him again I have a lot of questions to ask."

Rosina Claxton has more than questions.

She says that apart from the unprintable things she would say, "I would tell him, 'no more'."

*The camp is now split into several sections and owned by different residents, some who are in no way connected to the former cult. These properties are private and not open to the public.