The Church of Scientology has shifted tens of millions of dollars into Australia, which has become an international haven for the controversial religion where it makes tax-free profits with minimal scrutiny.

The finances of the Church of Scientology, founded by US science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard in the 1950s, have been almost entirely shrouded in secrecy since its inception, but an investigation by The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald has uncovered the most detailed financial information available anywhere in the world.

The international Church of Scientology has shifted tens of millions of dollars into Australia.

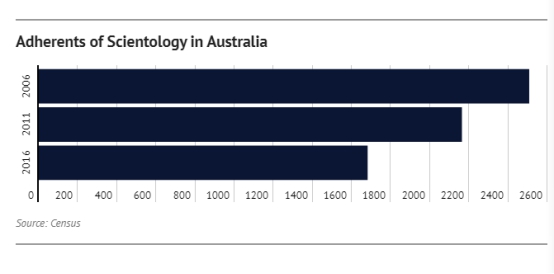

The figures reveal a big increase in the church’s wealth in recent years, even though census data shows it now has fewer than 1700 adherents in Australia – down by one-third in a decade.

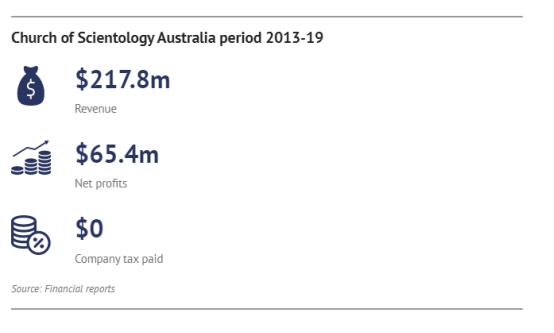

An analysis of the church’s financial accounts and elaborate corporate structure reveals the not-for-profit Church of Scientology Australia made net profits of $65.4 million between 2013 and 2019.

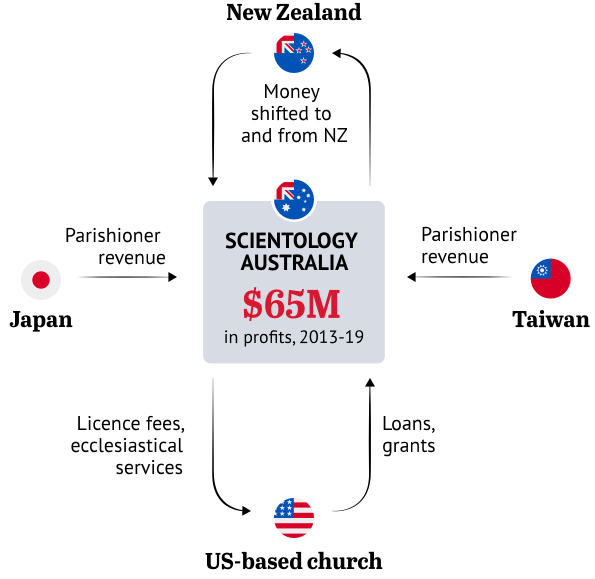

The reports show an array of cross-border money flows from cash-rich US-based affiliates. Its Australian operations received a $27.8 million loan in 2016 and a grant of $35.9 million from the United States in 2014 alone. In total, there were $78.5 million in grants and loans to Australia between 2013 and 2019.

The Australian church in turn paid millions in licence fees and $22.2 million in “ecclesiastical services”, and spent $8.9 million on books and artefacts from international arms of the church, while an unspecified amount of revenue from Taiwan, Japan and the Asia-Pacific region has moved through the Australian accounts.

The Australian church reported a profit margin of nearly 30 per cent, better than many companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange.

Scientology has been accused by former adherents of being a dangerous money-focused cult that has harassed its critics, exploited cheap labour, coerced women to have abortions and used violence. Former high-profile members, such as US actor Leah Remini, have become some of its strongest critics. Scientology has denied the claims.

“It’s a business masquerading as a religion,” said Mike Rinder, an Australian who rose to become one of Scientology’s most senior international executives and an official spokesman. He is now a prominent US-based critic. “They measure their success by how much money they have in the bank or [is] held in assets such as property.”

Church of Scientology International spokeswoman Karin Pouw denied this, saying Scientology “is in the midst of an explosive expansion in Australia, ongoing since 2007”, with new facilities in Melbourne, Sydney and Perth. She did not answer a question on whether she agreed with the 2016 census data which reported Scientology had fewer than 1700 followers.

Ms Pouw said the loans and grants from the US were to purchase church property and it had also been able to expand through “the generous donations of Scientology parishioners who use these facilities”.

“There is no accumulation of ‘profits’ as you suggest,” she said. “All of the church’s funds are dedicated to furthering its religious and charitable mission.”

The build-up of wealth is helped by Australia’s generous regulatory treatment of Scientology, its tax-free status and its protections as a religion after a landmark High Court decision in 1983. In much of the world, Scientology is not afforded that tax status or classed as a religion.

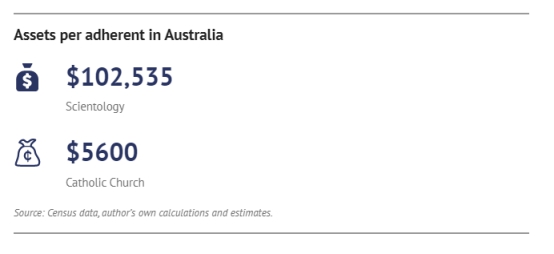

Scientology has built up enormous wealth in a relatively short time. An analysis by The Age and the Herald shows Scientology’s assets in Australia are worth $102,535 per adherent. By comparison, a 2018 Age investigation estimated all the entities related to the Catholic Church in Australia had wealth of about $30 billion, equating to an average $5600 per Catholic in Australia.

The Church of Scientology headquarters in Chatswood, Sydney.

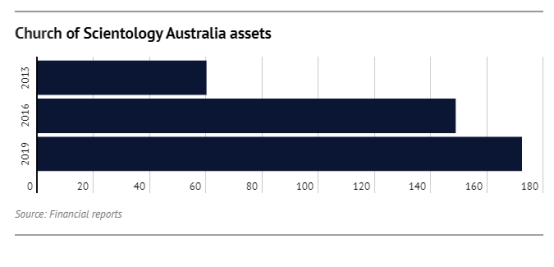

Figures for Australia show Scientology’s assets rose from $60.1 million in 2013 to $172.4 million in 2019, which included the building of its “Ideal Advanced Organisation” centre for the Asia-Pacific region in Chatswood, Sydney.

Figures for the UK, where it has about 2400 adherents, also show increasing wealth, with nearly $150 million in assets, a near tripling since 2013 as more than $50 million in loans was injected from the US-based church. The UK finances, including the ownership of assets, are reported through an Adelaide-based entity set up in 1977 and are also lodged with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission.

In total, $326 million of Scientology assets are now owned through Australia.

However, in Britain, where the church is liable for UK corporation tax, the profits are far lower and are offset by large debts to US and offshore entities of Scientology. Using internal debts to related offshore companies to reduce taxable income is a common tactic of multinational corporations.

Ms Pouw rejected this. “The UK church is engaged in its own building and renovations program, which accounts for the debt you refer to.”

Former executives and adherents say Scientology makes money in two main ways. It uses aggressive sales techniques and can charge followers tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars to progress through its courses and move through religious levels. It is also heavily reliant on large donations from extremely wealthy backers.

Scientology has attracted celebrities such as Tom Cruise, Elisabeth Moss and John Travolta. In Australia, there is Kate Ceberano and a slew of extremely wealthy backers. Billionaire James Packer was for a time a Scientologist, after being introduced to it by Cruise. One backer, US businessman Robert Duggan, has donated more than $US360 million ($475 million).

Australia’s tax and regulatory regimes are favourable to religions, but it is one of the few jurisdictions to require Scientology to report some financial data through its charity regulator. In the US, Scientology does not do so and the scale of its total wealth is hidden.

Melbourne Law School professor Ann O’Connell, an expert in the taxing of charities and not-for-profits, said that being established as a religion was an “easy” threshold to cross in Australia based on the 1983 High Court case.

“If charities file their annual reports [with the ACNC] and don’t have a protest in the middle of the CBD and just rumble on and get their tax concession, it’s a good system for them.”

Professor O’Connell questioned whether religions that did not provide charitable services – for example, hospitals or shelters for the homeless – should be eligible for tax concessions. “Something like Scientology just doesn’t seem to do that.”

Charities, including religions, in Australia have to pass a public benefit test but it is automatically presumed that religion is for the public benefit. To lose that status, a case would have to be made to the ACNC Commissioner, Professor O’Connell said. That’s a weaker regime than in the UK, which has no presumption about public benefit for religion. In the UK, Scientology has not passed the public benefit test and is not a charity.

Mr Rinder, who was executive director of Scientology’s office of special affairs, said the organisation was wary of regulatory crackdowns, particularly from the Internal Revenue Service in the US. He said this would probably explain some of the shifting of cash from the US, where they “generate so much revenue” to Australia and elsewhere.

Scientology’s Ms Pouw said that claim “is as ill-founded as it is incongruous”.

Long-term Scientology researcher Tony Ortega, a former editor of The Village Voice newspaper in New York, said the business model of ploughing money into offshore property, including in Australia, served another purpose for Scientology and its leader, David Miscavige.

“He knows he’s not going to get a lot of young Scientologists [to join] but he’s got these wealthy older people that have to be convinced that Scientology is on the right track,” he said.

Scientology’s church in Ascot Vale, Melbourne.CREDIT:JUSTIN MCMANUS

“The way he does that is the constant opening of new facilities around the world.”

Mr Ortega said the church’s business model had led to “this massive accumulation of wealth” and that no expense was spared on spying on ex-Scientologists or litigation.

“An honest accounting of what Scientology does with money should horrify people and throw their tax status into question,” he said.

https://www.smh.com.au/national/scientology-shifts-millions-to-safe-haven-australia-and-books-multi-million-dollar-profits-20210325-p57e18.html