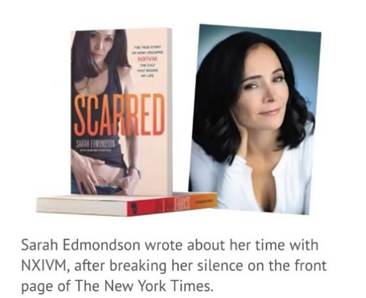

Sarah Edmondson has been asked why she joined NXIVM more times than she can count. But it wasn’t until 2017, standing naked in the home of a friend as the women around her were branded with a cauterising iron, that Sarah really started asking herself that question too. How did she get here? Why did she join the North American self-help cult?

Of course, when Sarah was on the inside, mixing with other celebrity members, following teachings she believed could change people’s lives, no one used the word “cult”. No one ever does.

People join communities, not cults, says expert Dr Steve Hassan, who has worked with Edmondson and other cult survivors around the world. People think only the stupid or naive are recruited. But Hassan says he’s found the opposite is often true: Cults target the best and the brightest – actors like Edmondson, wealthy and connected movers and shakers such as the doctors and government officials who joined Australia’s most infamous cult, The Family.

Edmondson let herself be branded with the other women that day in 2017. Later, they learned the symbol burnt into their flesh didn’t represent their secret women’s group at all but rather the initials of NXIVM leader Keith Raniere, who has since been sentenced to 120 years in prison for sex trafficking and other abuses in the cult.

Edmondson can tell you why she did it, and she can’t. “Part of it is still difficult to explain, even to myself.” But, when she left NXIVM, she used that brand as crucial pro

of to bring Raniere down.

So, why do people join cults, how do they work, and how do people break free?

What is a cult?

Lex de Man, the detective who helped uncover The Family and bring founder Anne Hamilton-Byrne to some measure of justice, thinks there are two main motives for any cult: money and control. “Particularly, control of people with money,” he says. Hassan adds a third: “Sex.”

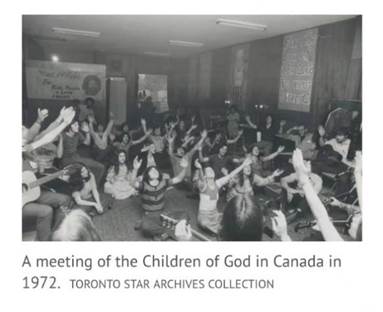

Thousands of groups such as The Family and NXIVM (pronounced “nex-ee-um”) have risen throughout history, but perhaps the one that has come to best define cults emerged in the US in the 1950s. Reverend Jim Jones originally built his “People’s Temple” in Indiana, combining elements of Christianity, spirituality and progressive socialism.

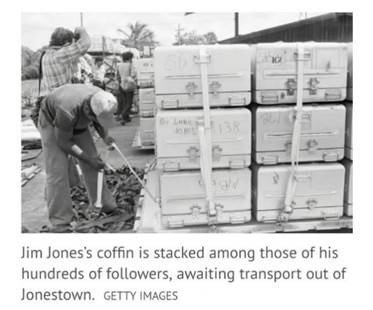

By the late ’70s, scandal and Jones’ own paranoia saw him move his followers deep into a South American jungle to a supposed utopian commune known as Jonestown. In 1978, when a US congressman and others came to investigate what had increasingly become a prison camp, Jones ordered their murders and made his most infamous directive: his followers were to join him in a mass suicide.

More than 900 people, including children, died when they were brainwashed or otherwise forced into drinking grape cordial laced with cyanide. Before 9/11, it was America’s single biggest loss of civilian life in a deliberate act. And Jonestown’s grisly legacy has come to represent not just cults but cult-like thinking more broadly: “They drank the Kool-Aid,” the expression goes.

“Destructive” cults tend to have three main aspects: a charismatic leader, a process where members are indoctrinated into the fold, and exploitation, be it economic, sexual or in some other form.

Not all religions are cults and not all cults are religious. Cults expand like pyramid schemes, with members often recruiting their own family and friends. Some literally operate as pyramid schemes, including NXIVM, which sold expensive self-improvement courses but under a system that ensured only a few senior trainers could ever make any money. (The fraudulent cryptocurrency OneCoin and the multi-level marketing scheme Amway have also been called cult-like.)

Many of the best-known cults have had a doomsday or violent undercurrent, as Jonestown did, where followers are coerced into performing horrific acts. Think of the Manson Family’s attempts to start a race war in 1969 by murdering wealthy, white actress Sharon Tate and four of her friends; or the Aum Shinrikyo cult that carried out the sarin nerve gas attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995, killing 13 people and injuring more than a thousand (the cult first tested out the gas on unfortunate sheep in remote Western Australia).

But even in cults that do not commit crimes against “outsiders”, abuse and punishment are often normalised within. There are allegations of child abuse in the Children of God cult founded in the US, for example , and, in The Family, the children stolen by the cult say they were routinely beaten and starved for “acting out”.

Often the abuse is psychological and financial. Hamilton-Byrne managed to talk followers into signing over millions of dollars in property and assets. She ordered members to divorce and remarry at her pleasure – even to give her their children to raise as her own.

Hassan ranks cults on his own continuum of undue influence, which is now used by some sex-trafficking experts internationally. We are all subject to some influence, he says, from the social media algorithms that help steer how we scroll and click to the politicians who play to our fears for votes. “The key question is free will,” he says. “Informed consent. Freedom of religion shouldn’t just mean the freedom to believe but the freedom to leave.”

“Other times, things are just a little bit culty. I mean, do you have CrossFit in Australia?” quips Edmondson. “But [the dangerous] cults are not just white robes and Kool-Aid and drinking goat’s blood either. It’s really abuses of power in all dynamics. It’s everywhere.”

While the US is often seen as the heartland of cults, many of the world’s major sects have deep roots in Australia too. Even the secretive cult at the heart of South Korea’s first major COVID outbreak, Shincheonji, has been recruiting students on the streets of Sydney and Melbourne.

When de Man was first investigating The Family, he recalls a sense of disbelief among the people he spoke to. “No one really believed this could happen in Australia,” he says. “Well, people need to understand what can go on in their own backyard.”

Why do people join cults?

Edmondson was a struggling actress in Canada looking for more meaning in her life when she opted for an unusual travel adventure. “I literally went on a ‘spiritual film cruise’.” There, she sat down next to acclaimed filmmaker Mark Vicente. He had just joined a group called NXIVM, and he thought it was unlocking his creativity. “I trusted Mark,” says Edmondson. “Someone like the Jehovah’s Witnesses coming up to you on the street is one thing. But when you meet someone you really respect, and they say, ‘Hey, you might like this thing’. That’s different.”

There were red flags right away. Everyone had to wear sashes around their necks, graded like karate belts, and they called NXIVM leader Raniere “Vanguard” and senior teacher Nancy Salzman “Proctor”.

But, as Hassan explains, the cult was already challenging prospective members to ignore their instincts, to get out of their comfort zone and push aside their “hang-ups”. “You feel like you’re growing but it becomes a trap,” he says. At the end of the NXIVM three-day intensive, for example, there was a manufactured breakthrough waiting – a mix of the dubious hypnotherapy Salzman specialised in and the practice of “auditing” in Scientology, where members are encouraged to share their secrets and traumas. (Scientology has been branded a cult in countries such as France and Germany but is recognised as a religion in Australia, the US and Italy.)

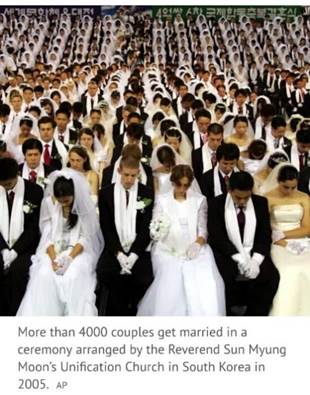

Hassan says hypnosis can muddy the waters even further between someone deciding to join a cult and being actively coerced. But often plain old deception will work just as well. No one ever tells you upfront what you’re getting into, he says, recalling his own recruitment to the Unification Church, sometimes called “the Moonies”, as a 19-year-old in the 1970s. “These two pretty women were flirting with me and inviting me to dinner.” Before long, he was fasting on the steps of the Capitol in Washington to protest the impeachment of Richard Nixon, who, as a friend of the group’s leader, Sun Myung Moon, was to be protected as an archangel. It was only when Hassan crashed a fundraising van, after two days of working without sleep for the Moonies, that he reconnected with his family and saw the kind of life he had been living – all for a man who wasn’t the messiah he claimed to be.

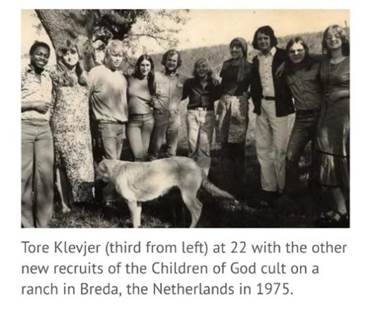

Tore Klevjer was 22 and backpacking through Europe when he was drawn into the Children of God. “I was very much at that crossroads, wondering what to do with my life,” he says. He left 11 years later with his young family and is now a counsellor in NSW helping other survivors, while running Australia’s main support group, Cult Information and Family Support (CIFS).

He says cult recruiters home in on people’s vulnerabilities. “Like any good salesman, they find out what you want and tailor their message to it. After joining, you learn the tricks as well.” Perhaps someone senior will take a special interest in you. Or you’ll score an invite to what cult experts call “high excitement” activities – such as the week-long festivities NXIVM put on each year called “V Week”.

Edmondson, who also became a star recruiter for her cult before getting out, says the tactics are similar to the love bombing experienced by domestic violence victims. “It always starts with the flowers and the chocolates and the romance,” she says. “And then there’s one moment, one underhanded comment or something that makes you go: did they really say that? But you don’t want to see it.[With NXIVM] I wanted the community. I wanted to feel like I was part of this special group who were changing the world. People like Keith [Raniere] use people like me who want to help others.”

Klevjer agrees that cults look for people who can sell the image of the sect, not just those who will buy it. But there’s a cult for everyone, he warns. “So maybe you won’t get drawn into a religious cult but what about meditation or self-development or even something that promises money? Everyone has a trigger.”

In the internet age, cults can wield power beyond a secluded commune. Many experts, including Hassan, consider QAnon a cult, for example, though it has no clear leader, save the anonymous “Q”, who first ignited the viral conspiracy theory on a message board in 2017.

“All people are hungry for community, to belong,” says Klevjer. “And especially in these unstable times, the world has become real shades of grey. People gravitate towards black and white just to try and keep their sanity, I think.”

Who are cult leaders?

The pull of a particular leader is often why people fall into a group’s orbit too. De Man didn’t meet Hamilton-Byrne until she landed on the tarmac of JFK airport in handcuffs in 1993. After a police raid had rescued stolen children from the cult’s secluded Lake Eildon property in 1987, de Man had spent years piecing together a case against Hamilton-Byrne for abuse, fraud and more, even teaming up with the FBI to hunt her when she fled overseas. Now here she was, “the most evil person I had ever known”. “I opened the door of that police van,” he says. “And inside was just this little old woman in shackles, without her makeup or her wigs.”

Yet three decades earlier, when the then-renowned physicist Raynor Johnson met Hamilton-Byrne in Melbourne, he thought the glamorous blonde at his door was the reincarnation of Jesus Christ.

Hamilton-Byrne was actually the daughter of a woman who claimed to speak to the dead and had spent much of her life in asylums – sad beginnings that she spun into a tale of spiritual pedigree. In the 1960s, she began teaching yoga to wealthy middle-class women – just as eastern spiritualism was sweeping west. Johnson was her first big recruit. “His name opened doors,” says de Man. She also preyed on the mentally unwell. At a private psychiatric hospital owned by a cult member, visions were manufactured by dosing patients with LSD, one of the most powerful hallucinogens and then legal for psychiatric care. “She’d appear in the doorway in a flowing white gown literally with a bucket of dry ice behind her and people thought they were seeing Jesus Christ,” de Man says.

She amassed a loyal army – well-placed people who could help her steal children with phony adoption paperwork because they believed she was raising them for a divine life. “A cult doctor would hand a child to a cult nurse, to a cult social worker, to Anne,” de Man says. “And, yes, in her heyday, she was very appealing to men. She was well-spoken, clever. Anne had presence.”

Hamilton-Byrne was convicted of only fraud in the end, paying $5000 in fines. She died in 2019, aged 98, with dementia (“and three days later, she didn’t rise again”, de Man adds.) But she remains infamous as one of the few female cult leaders to have emerged globally. “Ninety per cent are men,” says Hassan. Still, they seem to all share common traits, chief among them a “malignant narcissism” and a lack of empathy for their victims.

Most leaders were in a cult themselves, Hassan says, “whether that’s an authoritarian family or something or an actual cult cult. And cult leaders study other cults. We know Jim Jones read [George Orwell’s] 1984 and it was like a bible for him on how to run a cult.”

Keith Raniere, who told NXIVM members he was the smartest man in the world, stitched together the multi-level marketing tactics of Amway with Scientology and covert hypnosis. L. Ron Hubbard, the sci-fi author who founded Scientology, is said to have studied religions and sects extensively.

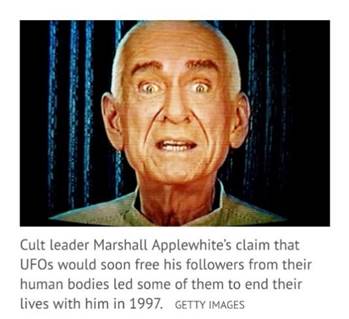

While most cult leaders seem to be liars preying on the faith of their followers, psychologists say some have appeared to buy their own delusions, as in the case of Heaven’s Gate in San Diego, the first big cult of the internet era that ended in the mass suicide of 39 members in 1997. Leader Marshall Applewhite claimed to have had a near-death experience that convinced him UFOs would soon arrive to liberate humans from their bodies to a higher existence.

What’s it like in a cult? Why do people stay?

A cult is like a black hole – the closer you get to the centre, the greater the pressure. What may seem benign on the outer rings can disguise darkness within. “Most people are fringe members,” says Hassan. “They have no idea what’s going on at the top. And if they look at the group from there, they think, nobody’s controlling me, I’m just meditating twice a day.”

Meanwhile, for those close to the centre, abuse is often secret. In NXIVM, for example, no one but those handpicked by Raniere and his right hand, Smallville actress Allison Mack, knew about DOS, the elite women’s group where senior members recruited others (including Edmondson) as their “slaves” and branded them.

“We had to send collateral – nude photos, damaging secrets – to be let into this mystery program,” Edmondson says. “Some of it was ridiculous, like the deed to my house – that was never going to happen – but I played along to bide my time.” Even when Edmondson began to see that DOS was not the life-changing self-development course it had been sold as, she still had no idea other women were being ordered to have sex with Raniere until her friend, Mark Vicente, rang to warn her.

Hassan says being in a cult can often give someone a kind of dissociative disorder, where they can think one thing, rebelling internally as Edmondson often did, and yet behave in line with the cult. “There was the old Steve Hassan who wrote poetry and liked girls and was going to teach English,” he says. “And then I got recruited into the Moonies and now Moon [the leader] and his wife are my true parents, and I had put on a three-piece suit and tie and cut my ponytail off. This cult self-oppresses your true self.”

But the extent to which cult control renders someone incapable of making their own decisions is a vexed question in academia. For those who have committed crimes while under the influence of a cult leader – such as the Manson Family murderers and senior NXIVM figure Allison Mack – brainwashing has not succeeded as a defence in court. Still, in the case of the Manson Family, Charles Manson’s powerful control over his sect saw him serve life in prison for first-degree murder despite not physically taking part in the killings himself.

Certainly, cults coerce their victims, isolating them from family and friends and keeping them too busy and stressed to examine things closely. In the Children of God, Klevjer describes days spent memorising scriptures, hitting the street to recruit and doing menial, often pointless, chores before it all began again before dawn. Living overseas in the commune in the days before the internet, he was already struggling to stay in contact with his family but was further pressured to renounce his father (a Christian).

In NXIVM, Edmondson was also living on “a hamster wheel”, with budgets constantly tight and pressure to ignore friends on the outside. “We were told, if you feel upset, that’s on you. So if the leader has upset you, why not choose to feel joy? You’re a Buddha under the tree, basically. It’s so unhealthy. I still find it hard to relax sometimes.”

How do people get out of cults?

Most people leave cults on their own within a few years, Klevjer says. Edmondson had been in NXIVM for more than a decade when long-nagging questions became a flood. “All of a sudden, everything made sense,” she says. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s not only what people have said in the past. It’s worse.’”

She and her husband, Nippy, left quickly then with Vicente, and they weren’t the only ones. Their connections in the acting world had drawn many of the Hollywood names, such as Mack, to NXIVM in the first place (“I still carry that guilt”, says Edmondson) and now their influence was seeing people desert the cult in droves. “We started calling people, telling them what was happening,” Edmondson says, drawing on the same skills that had made them such good recruiters and forming a kind of community of survivors every bit as strong as the bonds that had drawn them to NXIVM. “You have to move slowly, you have to ask questions like Mark did to me,” she says. “He’d ask, ‘How do we know that Keith is who he says he is?’”

Re-engaging someone’s critical thinking, helping them realise the truth of a cult on their own, is a key way to help them out, says Hassan, whose first book on cults helped many other renowned experts escape their own sects. Of course, in “the old days” it wasn’t so gentle.

After Jonestown exposed the danger of cults to the world, concerned families in the US sought court orders to hold a person for a few days to “deprogram them”, introduce them to ex-members, and talk through the concerns of their loved ones.

“It worked,” says Hassan, who was “deprogrammed” shortly after his car accident briefly knocked him out of Moonie life. He has spoken of the terror of having his worldview shattered by the polite team of “deprogrammers” who arrived at the door that day but also of having space to rest and see his family, to think again. He went on to study psychology and lead interventions himself.

“Most people left once they were exposed to the real world again,” he says. “But the cults got other religious groups on board to call it a violation of people’s rights so I started to try voluntary interventions instead, like we do for alcoholics, luring someone home for Grandma’s birthday and then surprising them.” These days though, he says, cults are wise to this approach too. “They’ll ban visits home to family or send a ‘cult buddy’ along.”

Both Hassan and Klevjer, who also helps the families of cult members, advise people not to take a confrontational approach but rather to arm themselves with knowledge of the cult and mind-control tactics.

“It’s really hard not to charge in and save someone, but often that’s the worst thing you can do,” Klevjer says. Police, too, find it difficult to get involved when someone is of age and capable of making their own decisions, he says. “There’s religious freedom laws that shroud them. And, of course, some cults love to take people to court or [use their people power] to harass or blackmail.” (The “collateral” of nude photos Edmondson was ordered to give over were later leaked online by NXIVM when she went public with abuse allegations and revealed her brand on the front page of The New York Times.)

The main thing is to keep the relationship with your loved one intact, Klevjer says. It might become their lifeline. “You really need the support of our family and friends when you leave. You don’t want to think, I’ll be on my own, they’ll say, ‘I told you so.’”

When Klevjer and his wife left the Children of God, they had five kids, another on the way and just $500 dollars. “We had nothing. We ended up back in [Sydney] in a broken-down old place that used to be a bikie hangout, holes in the walls but, of course, to us, after never having anything of our own in the cult, we felt like millionaires.”

Joining a cult is like falling in love, he says. “We don’t want to listen to what our friends say because we know how we feel.” And cults play on this, telling members they don’t have to listen to their families anymore. “They say the devil or the forces of evil, or whatever they call it, are working against you because you’re doing the right thing here,” Klevjer says. “So they prepare people for attack. When a family falls into that trap, it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“But if you’ve got people who care about you, who don’t want anything from you, saying, ‘I don’t know about this,’ then it’s probably a good warning sign that you should take a step back, Google this group or this person and see if there’s any fire where the smoke is.”

For those born or drawn into cults young by their parents, getting out can mean leaving behind the only family they’ve ever known. “Suddenly, they’ve got to find their way in society by themselves,” says Klevjer. “Not knowing what’s true: is it what the cult says or the world?”

De Man, who remains close to many of the children who escaped The Family, says acknowledgment of what happened to them is crucial. “They didn’t sign up for any of it, how they were raised. They need help.”

Meanwhile, walking those who were recruited through the process of how it was done, how the cult operated, can help free them from the shame they carry. But, without some form of exit counselling or education on cults, experts warn people will often fall in with another.

If Edmondson hadn’t escaped a cult herself (one labelled by the media as “the sex cult” no less), she admits that she wouldn’t understand how someone could be sucked in either. But that knowledge is a powerful protection. People who walk around thinking it’ll never happen to them are more vulnerable, she says, whether to a cult or a shady business deal or a gaslighting boss.

“Anyone can be fooled,” agrees de Man.

To spread awareness, Edmondson and her husband have started a podcast featuring experts and fellow cult whistleblowers. “That’s been really healing, connecting with other survivors,” she says. “I feel less alone. And I get to help people, which is what I actually love to do the most.”

Although Edmondson had her brand surgically removed two years ago, the “moral scar” of what happened in NXIVM remains.

“I want people to know that they have a way out,” she says. “There’s a community out here too.”

Original Website: https://www.smh.com.au/national/why-do-smart-people-join-cults-and-how-do-they-get-out-of-them-20220315-p5a4uh.html