· Nearly 40 per cent of respondents to a survey said they had lost trust in religion, as some say they see no reason to visit Buddhist temples any more

· Problems caused by ‘new religions’ such as Aum Shinrikyo and the Unification Church are still affecting Japanese society, an analyst notes

A Buddhist monk prays at a temple on Mount Koya in Japan’s Wakayama prefecture. About two in five people interviewed for the survey said their sense of trust in religion had declined in the past two years. Photo: Shutterstock

A study by a major Buddhist temple in Tokyo has revealed a growing distrust of religion in Japan, a trend analysts suggest is the consequence of religious cults that have in the past used violence to advance their aims – and the more recent scandal surrounding the infiltration of politics by the Unification Church.

A knock-on effect of this loss of faith, they say, will be the inevitable weakening of Komeito, the junior partner to Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in Japan’s ruling coalition.

Komeito was founded by lay members of Buddhist religious movement Soka Gakkai in 1964 and is considered to be the new religious movement’s political wing.

The survey on religious trust, carried out by the Tsukiji Honganji temple, revealed that 39.7 per cent of the 1,600 people interviewed said their sense of trust in religion had declined in the last two years.

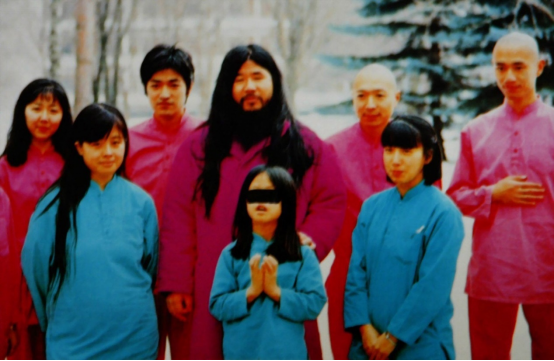

Members of the Aum Shinrikyo religious cult that was behind the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system, including cult leader Shoko Asahara (centre, back), are seen in this undated file photo. Photo: EPA-EFE

The results were most visible in women aged between 18 and 49, with around 50 per cent saying they have less trust in religion today than in the past, although a more exact determination is difficult as the survey was the first of its kind.

Close to 35 per cent of all the respondents said they felt “uncomfortable” with religion in general, although that fell to around 10 per cent when they were asked specifically about Buddhism.

Most of the respondents under the age of 60 also indicated they had “no reason” to visit a Buddhist temple, a statistic that observers say will prove worrying for the religion in future.

“In the past, there have been numerous incidents and social problems that were attributed to so-called ‘new religions’ and the impact of those problems can still be felt to this day,” said Toshimitsu Shigemura, a professor of politics at Waseda University. “To most ordinary people, these religions and their aims are very questionable.”

One of the most notorious “new religions” was Aum Shinrikyo, which carried out a sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995 as it sought to overthrow the Japanese government. Followers of cult leader Shoko Asahara were found guilty of a litany of crimes, including murder, and 13 were executed – although thousands of adherents to the cult’s beliefs subsequently joined two splinter groups after Aum was disbanded.

While Aum may have been the most infamous “new religion” to gain a following in Japan, several hundred groups have emerged since the nation began to experience social turmoil and rapid industrialisation in the 1860s.

Concern over the activities of such groups was heightened last year when a man used a home-made gun to kill former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as he was speaking in the city of Nara.

The assailant, Tetsuya Yamagami, told investigators that he attacked Abe because he and his party were linked to the Unification Church, which he blamed for convincing his mother to make lavish donations and bankrupting the family.

Dozens of politicians were later revealed to have links with the group, including no fewer than 10 of the 20-member cabinet, and there were suggestions the church had lobbied for some of its policies to be adopted by the government.

“Public distrust of religion seems to be growing stronger as a direct result of the killing of Abe and the media coverage of the Unification Church,” said Sayuri Ogawa, an outspoken critic of the church who uses a pseudonym and is trying to help others escape from a movement she says is “evil”.

Ogawa also highlighted “reports on the malicious solicitation of donations and human rights violations by the Jehovah’s Witnesses group”.

“In the past, religion was necessary for a community of people, but now we can connect with many people through the internet,” she said. “Also, when a problem arose, religion used to be there to help ordinary people, but that is no longer the case. I think it can be said that people no longer need religion.”

Shigemura, the politics professor, said that while in the past religious groups might have helped the poor, that assistance was no longer needed in a relatively wealthy country like Japan.

“It has got to the point that many people no longer believe in the reasons that religion was previously necessary and that has become a lack of trust in religions’ aims,” he said.

If people were turning their backs on religion, Komeito could struggle to find more followers in a nation where the population was also in decline, Shigemura said.

“Membership of the party is falling and so its influence on the LDP and government in general is weakening,” Shigemura said.

“The LDP will eventually reach the point where it can no longer rely on Komeito’s support and will have to find another political partner.”